A good author must make time to read and write every day. Just as competitive athletes train every day, rain or shine, to become the best, an author who aspires to be published must also make writing a daily discipline. And just as good athletes study their competition, published authors are usually voracious readers. The advice I’d pass down to aspiring authors is to write 1000 words a day, every day, and to read at least one book per month in their field or genre.

As part of my series about “authors who are making an important social impact”, I had the pleasure of interviewing Orlando Ortega-Medina.

Orlando Ortega-Medina was born in Los Angeles to Sephardic Anusim immigrants from Cuba, studied English Literature at UCLA, and has a Juris Doctor law degree from Southwestern University School of Law.

In August 1999, Orlando and his life partner expatriated to Canada in search of same-sex equal rights, and in 2005, taking advantage of Canada’s recognition of same-sex marriage, he and his partner were among the first same-sex couples to marry at Montreal’s Hotel de Ville.

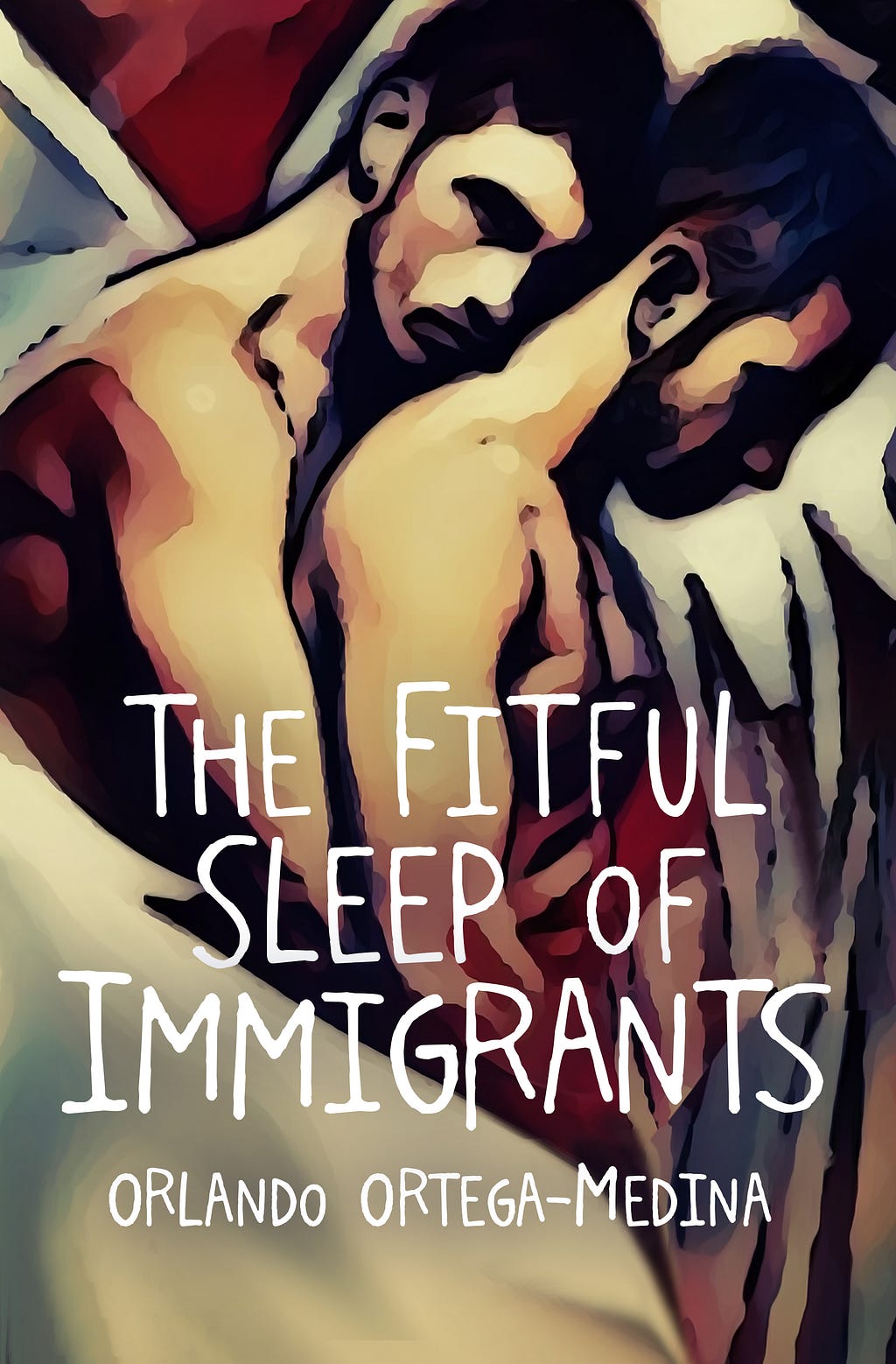

Orlando’s short story collection Jerusalem Ablaze was shortlisted for The Polari First Book Prize (2017). He is the author of three novels, The Death of Baseball (2019), The Savior of 6th Street (2020), and The Fitful Sleep of Immigrants (2023).

Thank you so much for joining us in this interview series! Before we dive into the main focus of our interview, our readers would love to “get to know you” a bit better. Can you tell us a bit about your childhood backstory?

Both of my parents were born in Cuba. They were raised in the same neighborhood in Havana and became childhood sweethearts. Due to the political upheavals of the 1950s, they fled the Cuban revolution and settled in Los Angeles, where I was born.

I grew up in a homogeneous, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant neighborhood in Southern California. We were notably the only Hispanic family on the block. So, from a cultural perspective, what was happening in my family home was distinctly different from what was happening just outside our doors in the homes of our neighbors and my schoolmates. First, there was the multilingualism of our household; then there was the food we ate, which was decidedly Cuban, but without the pork or shellfish; and then there was the issue of religion. Our neighbors were mainly evangelical Christians. We had no religion as far as I was aware.

When I was 10 or 11, my parents joined a Cuban Cultural Club that met about 30 miles away from where we lived, and I was finally exposed to other Cuban families and kids. Up until then, I thought the fact my parents were from Cuba explained why we were so different from everyone in our neighborhood. But when we joined the Cuban Cultural Club, I was shocked to discover just how different we were from other Cuban families as well. All of them were Roman Catholic, which, at that point, was something utterly foreign to me. And they ate different things from us as well. I felt like a foreigner among these people who were supposed to be like us. I understood we weren’t like the American families, but why were we different from Cuban families too? This question really bothered me for much of my early childhood, this sense of not having a clear understanding of who and what I was. I wasn’t like my neighbors; I wasn’t like other Cuban kids; I wasn’t even like my own parents who were raised in a different country from me. Thus, my childhood was one of constant challenge, uncertainty, and confusion. My self-perception was not clear.

On my thirteenth birthday, my paternal grandmother gifted me with a lovely blue and white knitted skullcap and a Star of David pendant, and she told me:

‘Our ancestors were Spanish Jews who were forced to convert in the 15th century. If this hadn’t happened, we’d be celebrating your becoming Bar Mitzvah today. So, in honor of our ancestors, I am giving you these symbols of your Jewish heritage.’

This disclosure was both shocking and exhilarating for a high-strung teenager who knew next to nothing about Jews or Judaism, much less about Spanish Jews. But it certainly explained a lot that had been troubling me about my family and our customs compared to other Cuban families.

My grandmother’s revelation sparked a restless fire in me that set me on a quest of self-discovery. The literary product of this quest is a body of work that explores the various strands of my identity. It includes short stories, screenplays, and, so far, four published books, the first of which was Jerusalem Ablaze: Stories of Love and Other Obsession (2017).

When you were younger, was there a book that you read that inspired you to take action or changed your life? Can you share a story about that?

Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth changed my life. The first time I read it, I was only twelve years old, if that. I found it by accident, wrongly shelved in the children’s reading room of our public library. After leafing through the first few pages, I decided to become better acquainted with it, so I hid it in my book bag and took it home. I wrote a whole story about its impact on me titled “Invitation to the Dominant Culture” which you can find in my short story collection Jerusalem Ablaze.

It has been said that our mistakes can be our greatest teachers. Can you share a story about the funniest mistake you made when you were first starting? Can you tell us what lesson you learned from that?

I naively believed that as I lawyer, I could make a reasonable living working part-time and the rest of the time I could devote to my writing career. As it turns out, the practice of law doesn’t readily lend itself to part-time work. It took me ten years after graduating law school to figure out how to fit writing back into my schedule. If I’d known then what I know now, I would have played my cards a bit differently when I started my legal career.

Can you describe how you aim to make a significant social impact with your book?

The main character in my forthcoming novel, The Fitful Sleep of Immigrants (2023), is a US born lawyer who is forced to choose between giving up his relationship with his Salvadoran life partner to remain in the United States and expatriating in order to stay together. Most people would have probably chosen the latter, as I did, but why should one have to make such a choice? Why should someone be forced to give up one’s homeland and career to be with the person they love just because they happen to be of the same gender? My aim is for readers to reflect on the injustice of such a situation and to encourage resistance of any attempts made to reverse the social and legal progress of equal marriage rights.

Can you share with us the most interesting story that you shared in your book?

The Fitful Sleep of Immigrants is a work of fiction consisting of several interconnected stories. If I had to select the most interesting of these, I’d have to say it’s the Salvadoran character Isaac Perez’s asylum hearing at the US Immigration Court in San Francisco. There, he describes his life in El Salvador during that country’s civil war and the harrowing event that drove him from his home, including his journey through Guatemala and Mexico and onward to the safety of United States.

What was the “aha moment” or series of events that made you decide to bring your message to the greater world? Can you share a story about that?

That moment for me was when the Toronto-bound plane carrying my life partner and me to our new life in Canada reached its cruising altitude, and I realized that we’d crossed the point of no return. It was then that I decided I needed to write a book about our experience. Once we were settled, I started work on an intended memoir. As I drafted the source material over the course of a long, dark Canadian winter, deeply bitter at having been effectively ejected from my country of birth, it became clear to me that a memoir forged in anger made for an unpleasant read. I was much too close to the material and lacked sufficient objectivity to produce anything better than 200,000 words worth of sour grapes. And so, reluctantly, I shoved the manuscript into a drawer and forgot about it. Fifteen years later, I came across the material, dusted it off, and began the process of re-imagining The Fitful Sleep of Immigrants as a novel, a format I felt better suited the subject. And so began its long journey from initial draft to innumerable re-writes to publication.

Without sharing specific names, can you tell us a story about a particular individual who was impacted or helped by your cause?

An early reader of my forthcoming novel recently emailed me to say that he was optimistic for readers younger than him as the literary canon evolves to better represent minorities of all types. He wondered if people of his generation were cognizant of the blind spots their cultural upbringing gave them. Looking back at his high-school years in the mid-90s, he reflected on, in his words, “liberal-minded teachers patting themselves on the back for preaching tolerance and acceptance of a ‘choice of lifestyle’, while overlooking, or even winking at, jokes from my peer group about our disdain for that lifestyle.” He went on to comment: “I can only imagine how damaging this all was to the gay and bisexual people in my social circle who, tellingly, all waited until years after we’d graduated to come out of the closet.” He was left wondering whether engendering empathy would have worked better to inoculate people like him from what he referred to as “homophobic preconditioning.” In conclusion, the reader commented: “I can think of no better empathy-building experience than the one your book offered me…[B]eyond simply enjoying a good story, I’m a better person for having read your work, and for that I thank you.” It’s feedback like this that validates my mission as an author and encourages me to keep writing.

Are there three things the community/society/politicians can do to help you address the root of the problem you are trying to solve?

- Support the passage of the Respect for Marriage Act.

- Resist any attempts to reverse Obergefell v. Hodges, which requires all US states to recognize same-sex marriages.

- Pass an Equal Rights Amendment to the US constitution with additional language added guaranteeing that equality of rights shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sexual orientation.

How do you define “Leadership”? Can you explain what you mean or give an example?

The best leaders in my view are those who inspire others to follow them rather than those who demand loyalty from their subordinates. These are usually people who did not originally seek to be leaders, but who humbly rose through the ranks by concentrating on doing the best job possible while showing empathy to those around them. A leader is a good listener and should always take into consideration the views of others before making their final decision. In times of emergency, when there is little opportunity to consult others, a good leader must trust themselves and have the courage to make the tough decisions, come what may, without fear of criticism.

What are your “5 things I wish someone told me when I first started” and why? Please share a story or example for each.

- You can’t do it alone. Marketable writing is a team effort between an author, their beta readers, their editor(s), and their publisher — all working in collaboration with each other. An author needs to be a good listener, taking on the advice from their team members, and not be too precious about their ‘baby.’

- A good author must make time to read and write every day. Just as competitive athletes train every day, rain or shine, to become the best, an author who aspires to be published must also make writing a daily discipline. And just as good athletes study their competition, published authors are usually voracious readers. The advice I’d pass down to aspiring authors is to write 1000 words a day, every day, and to read at least one book per month in their field or genre.

- Books are a tough business. A lot happens between placing your book with a publisher and your first royalty check. First, there’s further editing, proofreading, typesetting, cover design, printing, and promotion. All that costs your publisher money up front. Then there’s the marketing, sales, and distribution, which can absorb up to 60% off the retail price per each book sold. Finally, in the event a retailer orders your book for its shelves, which is not a given, they often have up to 18 months to send back any unsold copies to the distributor, which is a cost your publisher eats. My advice is that authors should learn all they can about publishing as a business to better appreciate all the work that goes into bringing their books to market and the costs involved.

- The most important person on the publicity team is you! Just because a publisher has bought the rights to your book doesn’t guarantee its success in the market. Someone must tell the world, otherwise nobody will know about it. And if nobody knows about it, nobody will buy it or read it. But what about the publisher? Won’t they promote your book? I hate to break the news to you, but even if you place your book with one of the ‘Big 5,’ there’s no guarantee they’ll have that much in their budget for the promotion of your book if you’re a new, unproven author. The lesson here is that you must be ready to do anything and everything in your power to lead the cheering section in the promotion of your book. Otherwise, it may fall flat on its face a week after its release, if not sooner.

- Don’t expect to quit your day job any time soon. Most of the published authors I know — and I know many — have a day job. Even those who have achieved some notoriety would not be able to support themselves from the royalties they earn from their books. My favorite creative writing professor at UCLA warned me about this early on. With graduation looming ahead, I found myself torn between applying to an MFA program and going to law school, which was another interest of mine. Either way, I intended to pursue a career in creative writing at some point. So, I sought counsel from the late Carolyn See (herself a writer), whose opinion I highly valued. Without hesitation, she advised: “Get your law degree first; write later.” So that’s what I did. Once I finished law school, I picked up from where I’d left off and carried on writing in my spare time. It took another twenty years before my first book, Jerusalem Ablaze: Stories of Love and Other Obsessions, was finally published. I’m thankful that I heeded Professor See’s advice.

Can you please give us your favorite “Life Lesson Quote”? Can you share how that was relevant to you in your life?

I’m particularly inspired by the following: “If you wait until you find the meaning of life, will there be enough life left to live meaningfully?” This gem is attributed to the Lubavitcher Rebbe. When I ran across this quote, I took great comfort in the idea that one could find meaning in the process of living.

Is there a person in the world, or in the US with whom you would like to have a private breakfast or lunch with, and why? He or she might just see this, especially if we tag them. 🙂

I’d love to sit down with Elon Musk and pick his brains about his vision for the future.

How can our readers further follow your work online?

You can learn more at orlandoortegamedina.co.uk and follow me on Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter @OOrtegaMedina.

This was very meaningful, thank you so much. We wish you only continued success on your great work!

Social Impact Authors: How & Why Author Orlando Ortega-Medina Is Helping To Change Our World was originally published in Authority Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.