Filmmakers Making A Social Impact: Why & How Filmmakers Le Ly & Tom Hayslip Are Helping To Change Our World

…For me, a documentary has to make people cry. You have to touch something deep inside, those three ounces of soul that connect you to God. If you touch that, and you feel the pain of someone who is suffering, starving, or sick, it resonates. That’s where a documentary can reach people. It has to uplift others and help them have a better life, better understanding, and a better future. A documentary is an education. If someone walks away and says, “Oh my goodness,” and keeps thinking about it months later, then it’s done its job. A good documentary has a lasting impact. It’s something that can be watched on channels like the History Channel, BBC, or KPBS, something that holds a place over time, teaching future generations. That’s the kind of documentary I hope we create for the world…

I had the pleasure of talking with Le Ly and Tom Hayslip.

Le Ly Hayslip is a Vietnamese-American author, memoirist, and humanitarian, whose life story is a compelling testament to resilience and reconciliation. Born Phùng Thị Lệ Lý in 1949 in Ky La — now Hoa Quy, a village in central Vietnam — she grew up amid the turbulence of the Vietnam War, witnessing firsthand the horrors that would later define her life’s work. At the age of 14, she was imprisoned and tortured for her revolutionary sympathies, an experience that deeply shaped her worldview and later influenced her writing and activism.

In 1970, Le Ly moved to the United States after marrying Ed Munro, an American civilian contractor more than twice her age. The following year, she relocated to San Diego, California, where she briefly settled into life as a homemaker. However, her time in America was marked by further hardships: Munro passed away in 1973, leaving her widowed with two young sons. Her second marriage, to Dennis Hayslip, a man plagued by depression and alcoholism, also ended tragically in divorce and his eventual death in 1982. Despite these personal struggles, Hayslip persevered, using her experiences to fuel her activism and literary work.

In 1989, she published her first memoir, When Heaven and Earth Changed Places: A Vietnamese Woman’s Journey from War to Peace. The book provides a vivid, nonlinear account of her childhood in Vietnam and her eventual return to the country in 1986, exploring themes of war, survival, and healing. Her second memoir, Child of War, Woman of Peace (1993), continued these themes, offering a more detailed narrative of her life in the United States and her complex relationship with both countries. Hayslip’s writing garnered widespread critical acclaim, with both memoirs adapted into the 1993 Oliver Stone film Heaven & Earth, in which Hayslip also made a cameo appearance.

In addition to her literary success, Hayslip has devoted much of her life to humanitarian work. Deeply moved by the devastation she encountered upon her return to Vietnam in 1986, she founded two charitable organizations: the East Meets West Foundation and the Global Village Foundation. Through these organizations, she has focused on rebuilding Vietnam by providing essential services such as shelter, clean water, medical facilities, and education. Hayslip’s philanthropic efforts have extended beyond Vietnam, reaching other parts of Asia, and her organizations have become vital bridges between the U.S. and Vietnam in the post-war era.

Her life’s work has been widely recognized, earning her numerous awards for her humanitarian and reconciliation efforts. Among these accolades is the 1995 California State Assembly award for her dedication to improving U.S.-Vietnam relations. Hayslip’s contributions to philanthropy and peace-building have also been acknowledged globally, including honors such as the Crockett Global Citizen Award and the Living Legacy Award from the Women’s International Center.

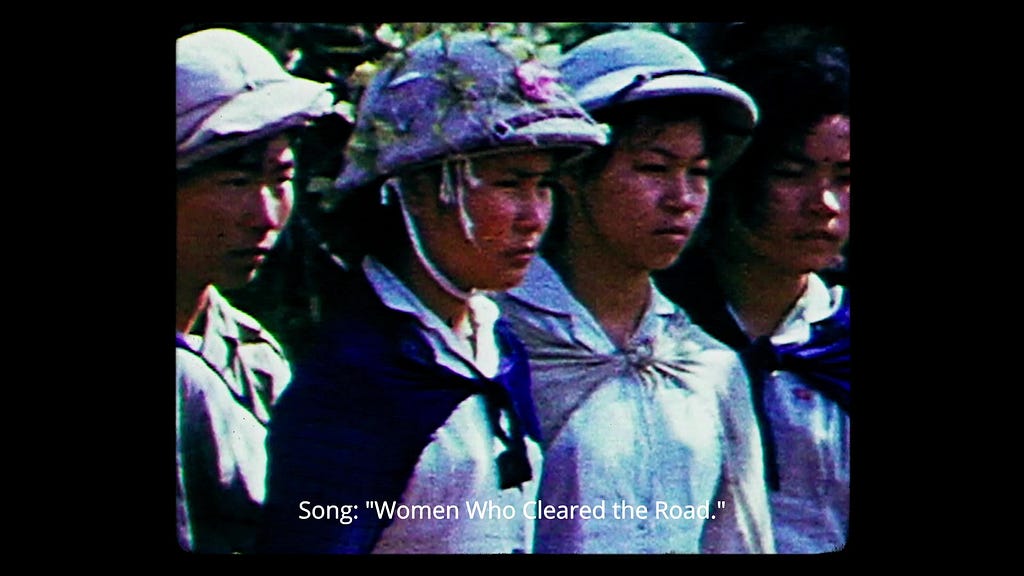

In recent years, Hayslip has continued her mission of promoting healing and understanding between the two nations, a goal that has taken on new significance with the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War. Alongside her son, Thomas Hayslip — an accomplished film producer known for his work on films like Oppenheimer and Twisters — she has co-produced a documentary titled Woman I Phu Nu. The documentary sheds light on the often-overlooked contributions of Vietnamese women during the war. These women, who worked as spies, bomb diffusers, and diplomats, played pivotal roles in shaping the country’s history, yet their stories remain largely untold. The film, produced by Matter Collective and Marble Mountain seeks to preserve their voices and legacy before these women are no longer able to share their experiences.

Filmed with a predominantly Vietnamese crew, Woman I Phu Nu offers unprecedented access to these women’s lives, reflecting the deep trust and respect Le Ly Hayslip has earned in Vietnam through decades of humanitarian work. Her return visits to the country, often accompanied by American veterans, have been a significant part of her ongoing mission to foster healing. These visits have facilitated projects like building orphanages and hospitals, as well as establishing educational programs, with many Vietnamese citizens expressing their gratitude by seeking her out during filming to personally thank her.

Le Ly Hayslip’s journey from a war-torn childhood to an internationally recognized author and humanitarian is one of transformation and resilience. Her work has not only provided a unique perspective on the Vietnam War but has also highlighted the power of reconciliation and cultural understanding. Now at 75, she continues to bridge the divide between Vietnam and the United States, ensuring that the voices of those who lived through the war, especially the women, are remembered and honored.

Thomas (Tom) Hayslip is an accomplished American film producer known for his extensive work on major Hollywood blockbusters. His credits include working on high-profile films such as Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (2018), Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 (2017), and Mission: Impossible — Rogue Nation (2015). With over 30 years of experience in the industry, Hayslip has developed a reputation for producing films alongside A-list directors and talent, often focusing on large-scale productions that attract global audiences.

Hayslip’s journey in the film industry began in the 1990s when he moved to Los Angeles, influenced in part by his mother, Le Ly Hayslip. Tom’s early years were shaped by a complex and challenging family background, blending American and Vietnamese cultures. Born in Vietnam in 1970 during the war, Hayslip moved to the United States with his family that same year. However, Le Ly felt lonely and homesick for her homeland. In 1971, they returned to Vietnam, but the ongoing war forced them to flee back to the U.S. in 1972. After this tumultuous start, the family eventually settled in San Diego, a military town with a strong Navy presence. This added another layer of complexity to Tom’s upbringing as the son of a Vietnamese war bride and an American civilian contractor.

Growing up as a Vietnamese-American in a predominantly white neighborhood, Hayslip struggled to reconcile his identity. His mother’s deep connection to her Vietnamese roots often manifested in her work within the community and her efforts to foster Vietnamese refugee children. Despite his initial reluctance to engage with his heritage, Hayslip’s experiences in Vietnam, particularly during a visit at age 16, gradually shifted his perspective. His exposure to the country and its people marked a turning point in how he viewed his identity and heritage.

Hayslip’s film career took off in Hollywood, where he carved out a niche in producing large-scale international productions. His notable projects include his work as an executive producer on Ferrari (2023), Oppenheimer (2023), and the upcoming Twisters (2024). While many of these films have been high-budget, entertainment-focused productions, Hayslip’s latest project takes a more personal and meaningful direction. Together with his mother, Le Ly, Hayslip co-produced the documentary Woman I Phu Nu, a film that highlights the underreported stories of Vietnamese women who played significant roles during the Vietnam War. The documentary, made with a crew that was 99% Vietnamese, offers unprecedented access to firsthand accounts from women who served as spies, bomb diffusers, and diplomats, among other roles. It aims to ensure that these women’s contributions to ending the war are recognized before their stories are lost to history.

The documentary project reflects Hayslip’s deepening commitment to stories that connect his heritage with his professional life. His partnership with his mother in this film represents a bridge between his work in commercial cinema and the more intimate, historically significant narratives of his family’s past and his country’s history. Le Ly Hayslip’s influence is palpable in the film; as a noted figure in post-war Vietnam, her humanitarian efforts and connections within the Vietnamese government opened doors during the production of Woman I Phu Nu. The documentary has taken on additional significance as the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War approaches, underscoring the timeliness of preserving these untold stories.

Hayslip’s body of work demonstrates a unique balance between Hollywood’s commercial demands and a personal, more meaningful exploration of identity and history. While films like Oppenheimer and Twisters showcase his ability to deliver high-octane, visually spectacular productions, Woman I Phu Nu stands as a testament to his evolving approach to storytelling — one that includes amplifying marginalized voices and exploring the complexities of war, memory, and cultural identity.

With numerous accolades to his name, including a 2023 Emmy nomination for Obi-Wan Kenobi, Hayslip’s career reflects both the scale of his achievements in entertainment and his ongoing efforts to contribute to projects with a deeper social and historical resonance. Through his latest work, Hayslip continues to expand the scope of his productions, delving into documentaries that not only entertain but also educate and preserve significant histories for future generations.

Yitzi: Thomas and Le Ly, it’s an honor to meet you both. Before you dive in deep, our readers would love to learn about your personal origin stories. Le Ly, can you share with us a story of your childhood and how you grew up?

Le Ly: I was born and grew up in a small village right outside of Da Nang, Vietnam, back in 1950. From 1950 to 1965, my life was in the village, caught between two wars. I had 2 water buffalos for pets — ducks, chickens, pigs, dogs, cats, birds. My friends were the coconut trees, the beautiful mountains, and the rice paddies. That was my fun. But we also had a lot of graveyards around us because of the war against the French. Then, the Americans came in 1960, picking up where the French left off, and the war started all over again. So, I was caught between South Vietnam, America, and North Vietnam. My family was revolutionary. We fought both against the French and against the U.S. So, I was a person who got caught in the middle of all of that.

Yitzi: Wow. So, you were in North Vietnam?

Le Ly: We grew up in central Vietnam, but my family supported Ho Chi Minh and North Vietnam, yes.

Yitzi: Wow. Can you share with us a bit about your experience during the war?

Le Ly: Yes. From 1950 to 1955, during my childhood, I witnessed much of what the French did to my village, including to my brothers and sisters. After the French were defeated at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, my brother and brothers-in-law left for the North in 1955. That same year, the South Vietnamese government, with the help of the Americans, established a puppet regime in the South. They came in and turned everything upside down again, just as the French had done for 100 years. So, the villagers rose and fought, just as we had fought for 1,000 years against the Chinese and 100 years against the French. Now it was the Americans and the South Vietnamese — no different. We stood up for our motherland, our ancestors’ graveyards, and all the beautiful things that made me happy. But the Americans were very powerful. To them, the war was a choice. For us, it was survival.

As a young girl, my family, being with the North, protected and supported the Viet Cong at night. But during the day, we also worked and supported the South Vietnamese and the Americans. We lived right in central Vietnam, caught between the North and the South, and that’s what the war was all about. I feel very honored to have survived and to be able to share the story of myself, my family, and the whole country of Vietnam. Almost every child born in those days grew up the same way, no different. But unfortunately, many could not share their story. I’m glad I can give them a voice.

Yitzi: Do you now live in the United States, or do you still live in Vietnam?

Le Ly: Oh, no. I came here with my husband, my son Tommy’s father, in 1970, and we lived in San Diego. But in 1986, I went back to Vietnam for the first time to see my mom. I saw what had happened there and what the war had done to the country and the people. That’s when I started helping the poor people. I also started writing my life story for the world, sharing what happened to our villages and making it into a movie. I set up two nonprofit foundations to help rebuild Vietnam, and that’s what I’ve been doing since 1986.

Yitzi: So amazing. You said you came in 1970? So, you came to the United States in the middle of the war?

Le Ly: That’s right, yeah. The Americans withdrew from Vietnam in 1973, and the war ended in 1975.

Yitzi: What were your feelings about coming to the United States, a country that was attacking your home?

Le Ly: That’s a big question people often ask me — how could my family support the North, and yet I live here in America? Well, nobody asked me back then. My husband married me without asking or caring about my background or where I came from. He visited my mom, who had moved out of the village and was living just outside Da Nang as a refugee in her own home, and that’s all he knew.

When I came to the U.S., it was very difficult. My English was very limited. My mother-in-law and my husband’s family were different from me. They were all in the Navy and looked at Vietnam from a different point of view. Both of his sons from other marriages had served in the Navy, and they had both been stationed in Da Nang. I met them there before I came to the U.S., so they understood a little about what was going on. They weren’t too much against me. But my husband’s brothers and sisters were a Navy family, and every night, the evening news would show the war crisis. They’d talk about Vietnam, and show what was happening on the battlefield.

Whenever they saw news reports of Americans dying, bodies being put in bags and carried onto airplanes, they would look at me and say, “Shame on you, your people are killing our people.” And then, when they saw Vietnamese villages burning, with women running out holding their children, crying, and in poor conditions, they’d look at me and ask, “Why do your people want to kill each other? Why do you like war?” I didn’t have the English to explain how I felt. I had no way to tell them, “That’s not what we want. That’s not what we asked for. We didn’t want outsiders to come in, take our land, destroy our villages, and kill our people.” If I could have said anything, I would’ve asked, “How would you feel if the Vietnamese came to San Diego and did the same thing to you?”

But, back then, I was just nobody. I couldn’t say anything. That’s how I felt. So, in 1971, I just couldn’t take it anymore. I didn’t like the U.S., so I left with my husband and children and went back to Vietnam. But in the end, I realized I had to be here to tell my story. Long story short, I came back in 1972.

Yitzi: OK, that’s great. You tell the story so well. Tom, I’m sorry to ignore you. Can you share with us a story about your origin, you know, growing up in the United States?

Tom: Mine was less traumatic than hers. But I was born in 1970 in Vietnam. We came here shortly after I was born, then went back to Vietnam, and, as my mom said, we came back to the U.S. in ’72 to stay. I thought it was ’73, but she said ’72. My dad died about three months after we got back to America. So, we left the war to come to America for peace, and then my dad died of emphysema. That left my brother, who’s three years older than me, myself, and my mom to fend for ourselves. My mom didn’t speak any English, and she was a war bride, basically. Growing up in San Diego, which is a big military town with the Marines, the Navy, and everything — it wasn’t a great place to grow up.

Being Vietnamese in San Diego was difficult, and it got even harder when my mom remarried. She married a Caucasian guy who became my stepdad, and we lived in predominantly white neighborhoods. We were the only Vietnamese family we knew in our area. My mom, though, would go meet other Vietnamese people because that was her community. To do that, she’d go down to Chula Vista, which was kind of the Vietnamese ghetto at the time. There, she’d hang out with refugees, Vietnamese monks, shop owners, and other people who had come over from Vietnam.

But for me, growing up, there wasn’t a strong sense of community. And being half-Caucasian and half-Vietnamese, I desperately wanted to fit in as an American kid. I played baseball, Little League, that kind of thing. But things weren’t easy, especially when my mom started fostering kids. Out of her kindness, she brought in foster children, starting with families she wanted to keep together. We ended up fostering three families of boys from Vietnam, as well as two other Vietnamese boys whose mom needed help. Then other kids came and went over time.

I remember the first family had Little Anh, Big An, Hiep, Hai, Dong, Chanh, and Tran, who were my older brother’s half-brothers. Then there were Jimmy and Michael, followed by Alan, my younger brother, and Jimmy, my older brother. So now we had eleven kids, plus my stepdad. He wasn’t really on board with it. I just remember him not knowing how to handle the situation, and there was a lot of tension in the house because, in his eyes, all these people from Vietnam were living in what was supposed to be “his” house. But it was our house too. I turned our home into a refugee camp for the children.

So, growing up in San Diego was like that. I worked hard to distance myself from what my mom was doing and tried to forge my path. But I still had to help with her foundation. I remember being in high school and having to work with her on fundraisers, which, as a teenager, wasn’t cool. I mean, who wants to work on a fundraiser to rebuild Vietnam when you’re in high school? I helped collect and load medical supplies to ship back to Vietnam.

Then, when I was 16 — although I think it was 14, my mom says 16 — I went to Vietnam for the first time. I saw the country, saw my grandmother, and visited the house in the rice paddies where my mom was born and where my grandmother had lived, fighting to keep it for generations. But at that time, I still didn’t think it was cool. I didn’t want to be a part of it. I just wanted to get back to the U.S., play Little League, and pretend I was just an American kid.

It wasn’t until I grew older, into my late teens and early twenties, that I had a change in perspective. I left San Diego and moved to Los Angeles to work in the film industry, thanks to connections made through my mom’s book and the movie that followed. That’s when I started to realize that being Vietnamese was cool. This was around 1990. I was 20, living in L.A., meeting people from all kinds of backgrounds. I met my first gay person. I met other Asians. I ate Thai food for the first time. And suddenly, people were asking me about my Vietnamese heritage. They’d say, “Oh, you’re Vietnamese? What’s the food like?”

For the first time, I had a bonding moment with others over things like, “Let’s go have a bowl of pho.” And I realized, “Hey, it’s kind of cool to be Vietnamese.” That’s when my perception of myself started to shift, and I began to embrace my identity as a Vietnamese American.

Yitzi: Amazing story. So, you have to tell us a bit about this new film you’ve created. Tell us why we have to watch it.

Tom: Well, so, you know, I make films for a living, and the films I make are popcorn movies, right? You go in, suspend disbelief, sit in a theater, laugh, cry, kiss fifteen dollars goodbye — all that stuff. That’s kind of the heartless world I live in, where I just make movies for the sake of movies. But my mom is always trying to do something more, something greater.

Last year, she started talking — actually, a friend of hers called me and said, “Hey, your mom’s trying to make this documentary in Vietnam.” At first, I wasn’t sure what she was up to, but I figured it was something important to her. As we talked more, I started to understand that she wanted to tell a story. And being the good son, I couldn’t let her walk that road alone because it’s going to be filled with challenges. More importantly, if she’s paying for it out of her pocket, that’s not how you conduct good business. So, I signed on to help her with this documentary.

With documentaries, what starts as one idea often evolves into something else as you uncover more along the way. Initially, my mom wanted to make a documentary about her sister Hai’s life. Hai was older than my mom, and I knew her from my trips to Vietnam. She was the wizened old village woman with black teeth who had lost her husband in the war. Afterward, she lived first with her father, then her mother until her mother passed away at 102. Hai herself later died at around 92 in the family house in the rice paddies. She essentially dedicated her life to caring for others. Once her husband was gone, that was all she did — she took care of their mother, tended the family land, and maintained the graves and the fields. I think my mom wanted to highlight Hai’s selfless story, especially her life in war zones.

But for me, as we worked on the film, the story evolved. It became less about Hai’s personal history and more about the country and the people who live there today. We found other people with their voices and stories, and those stories became just as important — if not more important — than Hai’s. So, it wasn’t just about what happened to Hai, but about what happened to the entire country and its people.

One of the driving forces behind making this documentary was my younger daughter, who had just turned 18. I wanted her to know these stories, to understand who she is and where she comes from. I didn’t want her to go through the same struggles I did to figure out what it means to be Vietnamese or to take pride in her heritage. It’s more than just a bowl of noodles or a few cultural moments. I wanted her to see the strength of Vietnamese women, the resilience of people who’ve endured trauma, and to grasp the deeper roots of her identity.

By bringing her to Vietnam and having my mom walk her through her own childhood and life struggles, she met these other women who had their place in history. They had lived through a moment in time, and their voices mattered. Through that experience, I hope my daughter found a greater strength in understanding what it means to be a Vietnamese person and the strength that comes from knowing your heritage.

Yitzi: So, Le Ly, can you tell us a bit about the message you want people to take away from the film? What are the takeaways you want people to have from the documentary?

Le Ly: So, you know, Vietnam is a country, not a war zone as people think, even though next year will mark 50 years since the end of the war. Some Americans still think when you mention Vietnam, they picture things like Hamburger Hill, Khe Sanh, Killing Fields, whorehouses, Saigon Tea, POWs, MIAs, refugees, boat people — all these labels they created for Vietnam. But we Vietnamese don’t know any of those words. Now it’s been 50 years, and I want to invite people, whether they’ve been to Vietnam or not, to come and see why they lost their sons, daughters, brothers, sisters, or loved ones in Vietnam. Come to Vietnam and meet the people, see it as a peaceful country with friendly citizens, not just a war zone like it was once portrayed.

I don’t want them to carry the image of war from the ’60s and ’70s any longer. We all know we won’t be here forever, so it’s time to change that image — for your healing, the healing of the family, the land, and society — so we can live in peace. That’s my main concern

Next year will also mark 60 years since March 8, 1965, when Americans first landed on Red Beach in Da Nang. And 10 years later, on March 29, 1975, they withdrew from Da Nang. I want to mark these two important dates with special ceremonies in Da Nang, on the beach. We’ll hold a prayer or candlelight vigil to honor those who lost their lives in Vietnam, and to help the souls of those who never returned home. That’s what I do — I take people to Vietnam every year for this purpose. We must have peace of mind while we live, to create a peaceful and calm society. That’s what we believe.

My message is that Vietnam is a 5,000-year-old country with its people, traditions, and culture. War just shaped who we are today, and it scattered Vietnamese people around the world. Now, many of us are coming back to help rebuild our motherland for future generations. So, I invite everyone to join me in that effort.

Tom: And what’s difficult — let me interject here — is, you know, as my mom said, she spent her life bringing people back to Vietnam to show them the country and its people. I remember that growing up. When she started her foundation, part of the mission was healing. She would bring Vietnam veterans back to the country to help rebuild hospitals, donate to orphanages, or contribute in other ways. She wanted to show them that it’s not just a war — it’s a country full of people with stories and history.

What’s amazing about Vietnam is that when you go there and try to talk to people about the war, their response is, “Why are we talking about that? Let’s talk about tomorrow.” Unfortunately, we don’t always find that same unity within the Vietnamese diaspora in America. With this documentary, for example, people’s first response has been, “Why are you only listening to people from the North? Why only Viet Cong voices? Where are the South Vietnamese voices?”

Our answer to that is, that there are already plenty of platforms for South Vietnamese voices. They live in America and around the world. The people from the North are still living in Vietnam, a socialist communist country and their voices haven’t been heard as much. So, if there’s a voice that needs to be amplified, it’s theirs.

Le Ly: Also, I want to mention the focus on women in the documentary. Women never had a chance to tell their stories because of our culture and the long wars we fought. Afterward, people were just trying to survive, and women didn’t have a platform to share their side. That’s what this documentary is about — bringing women out of the shadows to say, “This is what I went through. This is how I lived my life. This is how I helped end the war.” We wanted to bring up the women’s voices in our film because they’ve been in the dark for too long.

Yitzi: Amazing. I think many Americans today feel that the Vietnam War was a total waste — wasted resources, blood, and everything. Would you say that, or would you qualify it and say there was maybe some positive outcome from the U.S. involvement in Vietnam? Do you think anything positive came out of the Vietnam War?

Le Ly: Yeah, a lot of children, a lot of graveyards. And this guy here [gestures to Tom].

Tom: Positive — me. Without the war, there wouldn’t be me.

Yitzi: That’s great.

Le Ly: But, you know, again, there are two, three different levels, right? There’s a human level, a spiritual level, and a God level, OK? If you look at the human level, all we try to do is kill each other. How many more wars have happened after Vietnam? Did we learn anything? Nothing. So many bodies, money, energy, and resources are wasted. Instead of what I did — educating people so they can stay in their own country, make a good living, and be happy in their homeland — we go to war, and people end up as refugees or immigrants, leaving their families to come to the U.S. and face new challenges.

The consequences of the war are still with us today — not just 50 years ago. We still have problems like Agent Orange, landmines, disabled people, and many other issues that came from the war. That’s what it brought to Vietnam. Even the veterans who came back to the U.S. had similar problems — homelessness, and mental health issues. It used to be that when you saw a homeless person, they were often a Vietnam veteran. It was a shame. Things are a little better now, but it should never have gotten to that point. We should never have had that kind of war.

Yitzi: Amazing. Tom, you’ve famously helped create Oppenheimer, which is different, but there are some overlaps and some related themes. What are the similar themes between Oppenheimer and this documentary? What would you say are the takeaways that are similar?

Tom: I mean, honestly, they’re entirely different pieces, and I wouldn’t even venture to comment on Chris’s work. Let’s start with that.

What I would say, though, is that, you know, I think what was important to my mom in the women’s documentary was amplifying voices and stories of struggle. It started with wanting to tell her sister’s story and her struggles. And I think these kinds of voices need to be continually brought to the forefront, not just in Vietnam but all around the world. Whether it’s in war or not, there’s always going to be a group of people who can’t speak or aren’t allowed to. And as long as we keep bringing those stories to light, hopefully, the world will find some similarities in them. And through those similarities, we find some kind of greater cause collectively.

In making this documentary, and having my daughter be part of it, that’s where the American Dream documentary came in. That project was more personal, about how I felt I hadn’t done enough to instill in my daughter what it meant to be Vietnamese. I wanted to give her the traditions and culture I had to find on my own, as I explained earlier. Even though we’d taken her to Vietnam and tried — my wife and I — to show her what it means to be Vietnamese and to take pride in that, for her, it was just a place. She didn’t fully grasp it until she went and met people there, spoke to them, and heard their stories.

Only then did she realize, “Oh, wow, Vietnam isn’t just a bowl of noodles. Vietnam isn’t just my grandmother burning incense at Tet.” It’s more than that. It’s the young, twenty-something artist who just wants to create. It’s the seventy-year-old woman who needs her story told because she doesn’t know how much time she has left. It’s the transgender person, who, in most places, isn’t allowed to speak or be recognized, but still dares to raise her hand in Vietnam and say, “I have something to say.”

So, while we started the documentary with one idea, we came out with something bigger — hopefully, a platform that can help the world find similarities in their own stories by listening to these stories.

Yitzi: This is our signature question that we ask in all of our interviews. Based on your experience now, can you share five things that you need to create a successful documentary?

Le Ly: For me, a documentary has to make people cry. You have to touch something deep inside, those three ounces of soul that connect you to God. If you touch that, and you feel the pain of someone who is suffering, starving, or sick, it resonates. That’s where a documentary can reach people. It has to uplift others and help them have a better life, better understanding, and a better future. A documentary is an education. If someone walks away and says, “Oh my goodness,” and keeps thinking about it months later, then it’s done its job.

A good documentary has a lasting impact. It’s something that can be watched on channels like the History Channel, BBC, or KPBS, something that holds a place over time, teaching future generations. That’s the kind of documentary I hope we create for the world.

Tom: Well, for me, coming from the narrative world, I’m used to having a game plan. That’s a more straightforward creative path that I like to follow. Documentaries are a bit trickier. This is my second time trying to make a documentary in Vietnam. The first time, I was in my early 20s, and I got to the end of it not knowing what it was about.

What I’ve learned is you need a story. It doesn’t matter how broad the story is, you need something that compels people. So, that’s the first thing — find a compelling story. Then, find someone interesting in that story, someone others can relate to or find intriguing.

Next, you need someone to fund it. Time is money, and without time or resources, you won’t be able to follow the story properly. You also need time to let the story unfold naturally.

And finally, you need a platform for people to watch it. You can have the best documentary, but if it just sits on your hard drive or in a shoebox, it’s not doing anything. It only becomes a film when people watch it and it impacts them. Whether it’s on YouTube, a streaming platform, or even the old-school ways — like renting a VHS from a video store, which I used to do — you need a way for people to access it.

You don’t always need a Ken Burns-level, half-a-lifetime documentary. Just enough to introduce the audience to someone, help them understand the story, and take that journey with them. Hopefully, that journey impacts the viewer enough to make a difference in their own life or someone else’s.

Le Ly: And over the last 60 years, how many books, how many documentaries, how many movies have been made by people who went to Vietnam for a tour or two and came back to tell their story? But in Vietnam, we had no voice. We had no platform to share our feelings or tell our side of the story. Now, the younger generation — who’ve been educated here — are doing so well for themselves, and I hope they, like my son, can help bring Vietnam and America closer with the work we’ve been doing for the last 35 years.

It’s not just about the past; it’s about the future. Traveling back and forth, building connections, and making something better. When we look back, we can say, “Yes, this place used to be like that, but now it’s better.” That’s what it’s all about. Documentaries, our voices, our stories — they help us get our names, our faces, and our dreams to the next generation, who can do even better than we did.

Tom: I don’t even want to wait until I die to make it better. I’d rather do it now, so I can enjoy it. It’s always good to enjoy the fruits of your labor.

Yitzi: That’s great. This is our final aspirational question. Each of you is a person of enormous influence. If you could spread an idea or inspire a movement that would bring the most amount of good to the most amount of people, what would that be?

Le Ly: From 2024 onward, it’s a different world than what it used to be. You can see it in everything — from the weather to wars, and whatever else is happening out there. Each of us is responsible for what’s going on right now. We all have to think, “How can we give? How can we make a difference?” It starts with giving your time to society. I think more people should travel to see what life is like in third-world countries. Here in America, we have so much, and we waste so much. We overspend and chase money, and people are struggling. Prices are so high, and it’s getting harder.

If we can help others appreciate what we have if we can give more of what we have — whether it’s time, resources, or kindness — the world would be a better place. The more you give, the better you see the world’s potential, and then your children and grandchildren can have a better future. Otherwise, we’ll end up holding an empty bag at the end. That’s what I would call for: stand up, go out, and do something for humanity, for mankind, for the children and grandchildren who will inherit this world.

Tom: That sounds like a lot of work. So many different things to deal with. For me, it’s more straightforward. I think we just need to be willing to look for the similarities between everyone and everything. It’s so easy to focus on differences. It’s easy to pick them apart, and that leads to strife, division, and all the other things we know too well.

But when we can find something familiar, something we all share, it connects us. We all know compassion, we all know empathy. That’s why I keep coming back to the idea of a bowl of Vietnamese noodles. Everyone knows what it’s like to sit down to a warm, comforting meal. We know what it feels like. Sitting across from someone, sharing a meal, and breaking bread — it’s something every human needs: sustenance, comfort, understanding, the basics.

If we can focus on that — on finding and appreciating the things we all have in common — it would make the world so much easier to live in and to get along in.

Yitzi: Amazing answer. How can our readers watch the two films? And how can they continue to support your work in any way?

Le Ly: Well, I’m sure we’ll have all the information available. We’re on Facebook — especially me. But there’s something I learned from billionaire Chuck Feeney, who gave away a hundred billion dollars. He said, “Give while you can see it, enjoy it, feel it, and see where the money goes. Don’t wait until after you die to give.” I agree, and I’d add, no, you can’t take it with you. You’re born with empty hands, and you’ll die with empty hands. So give it while you can. That will bring you happiness and joy, and it will give your life a meaningful cause. We believe in reincarnation, and what you plant now, you’ll come back to harvest later. You can’t harvest without planting the seed. You can’t have water without a well. You can’t have rice unless you plant rice. It’s all connected.

Tom: And you can’t watch a movie unless you know where to find it! So, I think with our distributor, Matter, they’re figuring out who our partners are. But, unlike some projects, these films are done and ready to be viewed. We just want to make sure we release them on platforms that can support what we want them to achieve.

You can learn more information at https://www.matter.is/womandocumentary

Yitzi: I want to thank you both for your extremely gracious time. This has been truly fascinating for me personally — a really fascinating interview. I learned so much. I wish you continued success, good health, and blessings. And I hope we can do this again next year.

Le Ly: Thank you.

Filmmakers Making A Social Impact: Why & How Filmmakers Le Ly & Tom Hayslip Are Helping To Change… was originally published in Authority Magazine on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.